1 Kings 19:1-4, (5-7), 8-15a

Galatians 3:23-29

Luke 8:26-39

“Who are you, O Lord, and who am I?”

It is said that a disciple of Francis passed by the great saint and heard him repeating this question.

Who is God? Who are we? There is nothing more important we can ask and the answers are myriad.

Who am I? We often begin our lives with a ready succession of answers—a son or daughter, a student, an employee, a spouse, a friend—our identities become attached to activities and roles, some chosen, some given.

Then there are the identities we discover, those forged by mutual love or experience or both. Identities can be made through a shared understanding of the world. They can be cultivated by how we spend our time or money.

There are political identities and social identities and sexual identities. There are religious identities and national and ethnic ones.

But when we ask, “Who are you, O Lord, and who am I?” None of these answers satisfy. We sense there is something deeper, some way in which the answer to one half of the question is the key to the other.

Who God is can seem a question too large for any of us, too dangerous, too uncomfortable. So we cut off that side and ask only, “Who am I?”

I’m at an age in which many of my peers are discovering themselves. To do this they are leaving marriages, places, communities. Some are elated at having finally found themselves. I’m doubtful it will stick because I’m doubtful that they have discovered anything more than another mask, an image in a trick mirror.

The self is not the kind of thing that’s found by seeking. As Wendell Berry offers in his poem, Amish Economics:

And my friend David Kline told me,

“It falls strangely on Amish ears,

This talk of how you find yourself.

We Amish, after all, don’t try

To find ourselves. We try to lose

Ourselves”-and thus are lost within

The found world of sunlight and rain

Where fields are green and then are ripe,

And the people eat together by

The charity of God, who is kind

Even to those who give no thanks.

To possess the self is to be possessed by one’s identities. That was the case with the man Jesus encountered among the tombs, a man whose mind and body had become the seat of many selves. What’s your name? Jesus asked. He could just as well have said, Who are you? Legion was the response, for this man was fractured into a multitude of identities.

There is a political undercurrent to this response. A legion was a Roman military unit, an occupying force. I’ve long thought of that occupation in terms of a military presence, but it goes deeper than that. All of us are occupied by identities, layers upon layers of them, each an invasion of the Empire of the False Self into our lives. We are possessed by political parties, by brands, by ways of life. But none of these answers the true question of our hearts, none of these move us any closer to who we really are.

The legion that occupied the man among the tombs were permitted to leave, entering a herd of unclean animals. When the people of his village found him, he was sitting calmly, clothed and at home in himself. In response to this liberation, he wanted to follow Jesus. It’s an enthusiastic and good response, but there is also danger in it. Perhaps Jesus saw that a life on the road with him would easily tempt this man into the the same fracturing of identity that had led him to his possession in the first place. Instead, Jesus gives him the harder mission of settling in his home town, of going to his own people and place and proclaiming God there.

Most of us are not so fractured. We are not possessed by legions, but we are still possessed. As Thomas Merton put it, “Every one of us is shadowed by an illusory person: a false self.” The false self is what we find for sell in the market places of image. It is the self we hold onto through the degrees we place on our walls, the credentials through which we seek to assure our worthiness. It is most of all the self we seek to cultivate all on our own, independent of God. As Merton writes, “to be unknown to God is altogether too much privacy.”

This is why St. Francis asked, “Who are you, O Lord, and who am I.” We cannot know our true self apart from God. To know who God is to know who we are.

“He looks at us from the depths of His own infinite actuality, which is everywhere, and His seeing us give us a new being and a new mind in which we also discover Him. We only know Him in so far as we are known by Him, and our contemplation of Him is a participation in His contemplation of Himself.”

These lines from Merton name the path of contemplation, the way in which our true self is found “when God discovers Himself in us.”

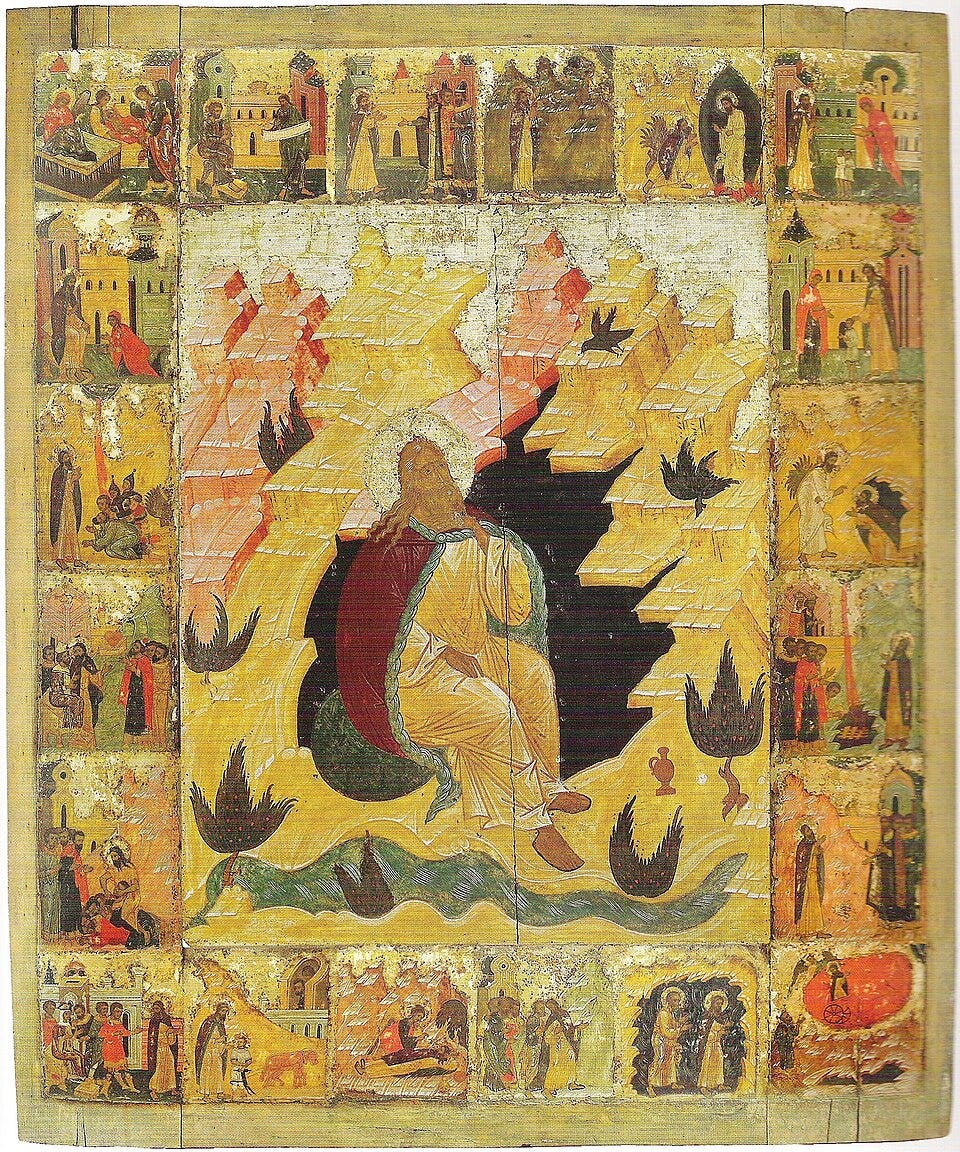

We lose ourselves when we lose this contact with God. Elijah experienced this. He was a man who was faithful and grounded, but the desolations of his ministry, the corruption of Ahab and Jezebel drove him to disconnection from his true source. He fled to the wilderness and wanted to die. But it was there that he met God and was restored. It was a return that came in solitude and silence.

Solitude and silence have been the best path to hearing God. Our minds buzz with the many voices inside and out that pour through our consciousness. Many of us can’t even go grocery shopping now without a steady flow of information and identity pouring through our headphones.

This may sound curmudgeonly but I say this as someone who spent a lot of time this week resisting the buy button on a pair of headphones that I can wear running—a time I often spend in quiet solitude.

Solitude is taking time to step away from the noise. But as the man in the tombs attests, simply being alone does not bring us back to ourselves. We also need to quiet our minds, to enter the deep silence that allows us to experience the still small voice of God.

God, for Elijah, was found in the sheer silence. And so it has been for many saints through the ages.

It was through this silence that Elijah discovered in his solitude that he is not alone. Caught in the worries of his life, the churning anxiety of his ministry, he felt abandoned. In solitude and silence Elijah discovers that not only is God with him, but that that there are 7,000 faithful people in Israel (a truth found just after the verses for this Sunday’s reading from 1 Kings). Elijah is part of an invisible community of the faithful.

And so it with us. We are, each of us, invited into a community far wider and richer than any human institution can provide, any political or social system can construct. The name of this community is Christ. This is the reality we are initiated into in our baptisms, the communion in which we participate through the Eucharist. It is through Christ that we become, as Paul reminds us in Galatians, children of God.

To join this community, however, we have to let go of our attachment to the identities that possess us. “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus,” Paul tells us. This does not mean that our identities no longer have a role in our lives, Paul was firm on his Jewishness, only that they are subsumed into the greater identity of Christ—the place where we discover who, in the deepest places of our personhood, we really are. For me, being male, Arkansan, a birder, a priest, etc. all still form how I live and move through the world. But in Christ, those identities are no longer things by which I’m possessed. Each is now opened to the discovery of a deeper identity in Jesus. In this identity I live in the freedom that comes in the knowledge that I can hear most readily in the silence: I am a beloved child, a participant in the life of God, who is closer to my truest self than I can ever grasp.

YES to this interpretation of the scripture regarding Legion. Jesus often cast out “demons”… and sometimes we think that is a thing of the past. I believe that demons are any ideas, beliefs, identities, or habits that take us farther from God rather than drawing us close. I wrote something on identity recently that parallels your words 😊

https://open.substack.com/pub/gatorprof68/p/what-i-want-my-kids-to-know-ab3?r=2loo1b&utm_medium=ios

Gosh, Ragan, I found this one very helpful. You reset my perspective when I seriously needed it.