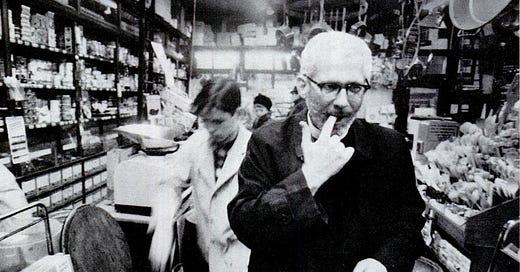

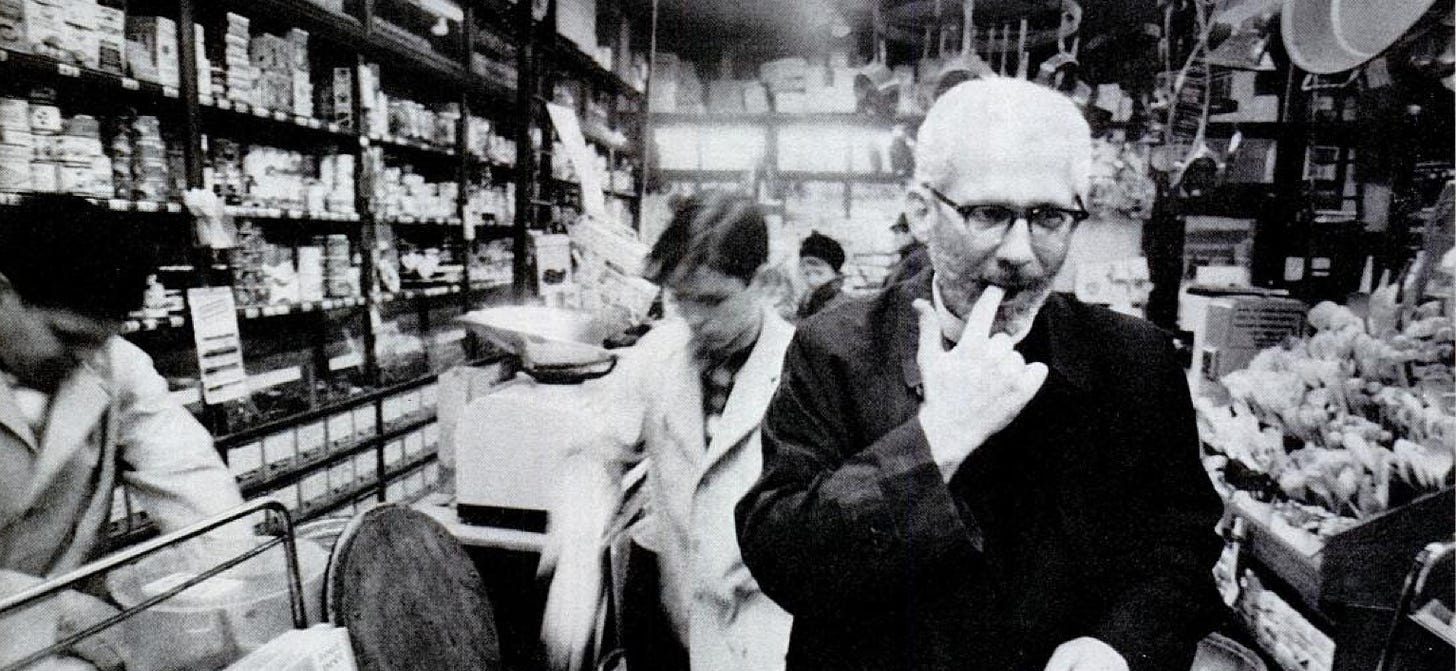

There is a recipe I’d love to try sometime. It’s called “Leg of Lamb for Eight People Four Times.” The recipe is at center the spiritual and culinary classic, The Supper of the Lamb: A Culinary Reflection by Robert Farrar Capon, and though I haven’t tried the exact recipe yet, its lessons have been echoing in my understanding for nearly two decades.

Through the recipe Capon, an Episcopal priest, works to offer an important distinction not only of the kinds of dishes, but also of the forms of eating. There is feasting, there is fasting, and then there is ferial eating. This last concept is a brilliant recovery of a concept nearly lost in Western tradition. Use the word ferial, as I’ve done off and on for years, and you’ll find both spell checks and editors aren’t sure what to do with it. The term comes from the Ecclesial Latin of the Catholic Church and was meant to mark any day in the liturgy in which no major feast was celebrated. Capon takes up the term to mark the common days in which there is neither a fast nor feast.

That there are to be different kinds of eating on different kinds of days is a nearly lost tradition. In so many ways we have flattened time and so flattened the rhythms of abundance, lack and the just-getting-by of ordinary existence. If we look at the world around us, however, no part of the given cycles of creation live by such a flat pattern of overfull plates every day and every season.

For those of us who live in the Northern Hemisphere, we are in the midst of a major transition time. Food is abundant—it is the time of harvest. My local farmer’s market seems to overflow with vegetables of all kinds, some of the summer varieties that have hung on along with many of those fall favorites like beets and carrots that carry the sweetness of cool nights. In the woods acorns crunch under foot everywhere and a wide variety of wild berries are there for the taking. Here it is still warm enough for many insects to be active and so birds are busy eating all they can. But we all know that this period of great abundance, is also a precursor to the winter when food will be harder to find. The total number of creatures active in the forest will diminish—most of the cold blooded reptiles and amphibians have already hibernated. Other animals will change their foraging patterns. American Robins, for instance, have already begun to gather into massive flocks rather than the dispersed summer territories they occupy during nesting.

I could go on, but the point is that creation has rhythms, and this goes for any place on the planet. Equatorial regions have their rainy and dry seasons and southern hemisphere countries of course have their summers and winters in reverse of those of us in the north. Why do we then not treat our eating in a similar way? Industrial agriculture and a global food market has a good deal to with that. I can eat apples all year around, but only now can I buy them from local farms in Arkansas. But there is also a wider flattening of our patterns in which all days see the over abundance of feasting for many of us without the balance of fasting or the ferial. Just as many have complained of their jobs occupying more of their days and even their weekends, there is a way in which our patterns of consumption have become a constant, everyday affair without much variation other than a weekend brunch.

Against this flattening Capon offers a traditional pattern to live and eat by, one that is rooted in the old patterns of the church calendar. Capon argues that feasting and fasting are twins, the one balancing the other. Instead of dieting, eating fake low-cal substitutes for our favorite foods, Capon suggests that we balance periods of abundance with periods of abstinence. And in the midst of those poles, our day to day eating should be ferial—simple meals that give us no more or less than our “daily bread.” An example of festal eating would be a steak with roast asparagus and mashed potatoes, a salad before and desert after. Fasting would be water, maybe some black coffee or unsweetened tea. Ferial eating is a pot of chili stretched with broth to make sure all the bowls get filled. It’s the stir-fry that assembles all the random vegetables in the fridge and makes sure everyone gets filled up with the bed of rice beneath. Ferial eating extends meals with the old art of thinning out and makes due with what’s on hand.

In a flattened culture where all too often every day looks the same, every meal is made and eaten in an identical pattern, I think we would do well to reclaim the pattern of feasting, fasting, and ferial eating. Capon calls on us to really feast when its time to do so, but also fast when that is necessary. Then, most days, we may skip the meat mostly and extend our meals into some delicious but simple fair that will fill our plates. On those days we make due and enjoy the simple everyday blessings of plain pleasures. In doing so, we will join in the greater rhythms of creation, the patterned dance of up and down and across, that brings life into its fullness.

Next week this series will continue with a look at how fasting might provide access to a different kind of energy, reflecting on Jesus’ own time of extended fasting at the beginning of his ministry.

Share this post