Disarming Evil with Revolutionary Patience

Some advice on dealing with enemies and evildoers from an ancient poet and Jesus of Nazareth | Epiphany 7, Year C

“Do not fret yourself because of evildoers.” The Psalmist seems to speak right through the centuries to our moment where, I for one, see a lot of fretting going on. Whether your news sources is the daily paper or podcasts, cable tv or social media, we seem to be in a frenzy of fretting.

Such fretting seems justified, given that there are true evildoers about, working toward agendas that hinder human flourishing and the survival of creation itself. Yet, in Psalm 37 we are told three times not to worry about these workers of woe. And not only are we not to worry about them, we aren’t even allowed the satisfaction of our anger—“leave rage alone.” Both worry and rage, the Psalmist tells us, lead only to evil. Instead, the ancient poet calls us to a different path. “Be still before the LORD, and wait patiently for him.”

Be patient. That may sound like a hollow and pious instruction before so many real and urgent injustices. Be patient sounds all too close to the “wait” that King heard from the white liberal pastors he wrote to from his Birmingham jail cell. “Justice too long delayed is justice denied,” King responded. And yet, King himself was a great practitioner of patience.

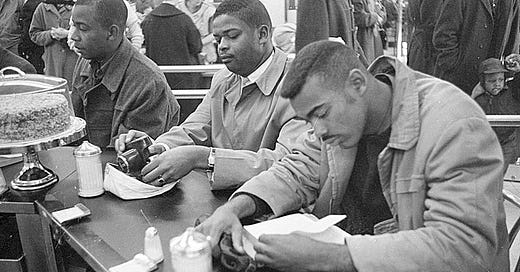

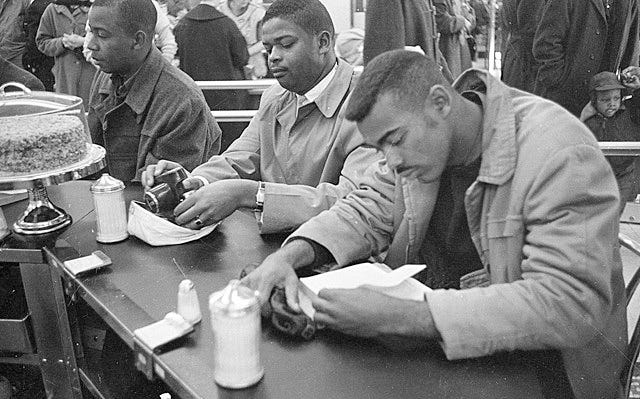

Being still at a lunch counter sit-in is something very different from mere passivity. As is turning the other cheek. These are acts of patient power, a confrontation with evil that shows that we are not afraid of “those who can harm the body.” The waiting found in our Psalm and even more so our Gospel is the sort that the liberation theologian Dorothee Sölle called “revolutionary patience.”

It is this revolutionary patience that is the foundation of Jesus’ call to go beyond fretting and to instead love our enemies. It is hard to overstate just how radical Jesus message is on this point. Few teachers in history have gone so far, and most of our greatest examples of courage in the face of real evil were direct followers of Jesus teaching on this point, from Gandhi to Martin Luther King, Jr..

But Jesus is not simply offering us a nice ethical teaching. Instead, as he states clearly, we are to love our enemies because God, who is goodness itself, pours out love and kindness toward everyone. Our call is to be imitators of God, and it is only through following the patterns of God’s life of goodness that we can escape the cycles of human violence that so easily turn the victims of evil into its perpetrators.

W.H. Auden in his poem “September 1, 1939” named a truth about the human pattern of dealing with evil:

I and the public knowWhat all schoolchildren learn,Those to whom evil is doneDo evil in return.

It doesn’t take a deep look at history to see those who have suffered injustice turn around and exercise it against others, often with profound moral blindness (simply look at the Netanyahu government). There is something about retribution and revenge that draws us into a dark circle from which we cannot escape until we have become the very thing we oppose. And yet, on the human plain, our imaginations are locked there.

The way out of this trap takes rescue from the outside, the power of God to exhibit and energize a different possibility. This is why we are to wait upon God. Not as a mode of inaction, but because we know that our own actions will only feed the monsters of our making.

What could we call this alternative to the logic of tit for tat? Grace. Grace is the gift that is offered even before reconciliation is achieved. It is the for-gift of forgiveness that unsettles expectations and creates possibilities where none could be imagined. Where is the grace in our world? Jesus asks us to look.

If we hope to find it in loving those who love us, Jesus says we’ll miss it. If we do good to those who do us favors, grace won’t be there. Jesus offer example after example of reciprocal relationships and asks, “what credit is that to you?” Credit is a strange choice of word on the part of the translators here and one that can keep us from seeing Jesus’ point.

As Ched Myers points out in his new study on Luke, Healing Affluenza and Resisting Plutocracy, the word translated as “credit” is the Greek word charis. This term is translated most other places in the New Testament as “gift” or “grace.” And when we read the term in this more common usage we can see that Jesus is not calling us to earn credit for how we behave, but is instead inviting us to live into the gift economy of God’s way. “The purpose of this teaching,” writes Myers, “is to push listeners beyond the conventional ethos of balanced reciprocity to a cosmology of grace.”

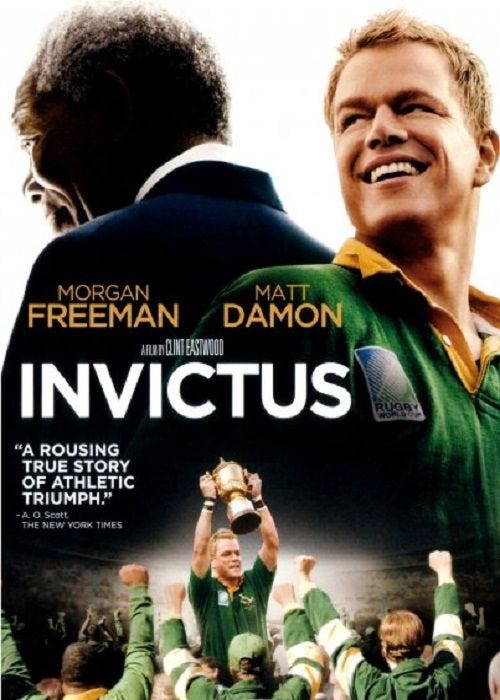

This is all nice theory and language study, but we should ask, how can such love of enemies actually show up in the world? What does the cosmology of grace look like in real communities? I found an answer the other night when my family spread across our curb-collected couch to watch the 2009 movie, Invictus. The film tells the story of Nelson Mandela’s transition to the presidency in post-apartheid South Africa, and his surprising work to bolster the Springboks, South Africa’s national rugby team. Rugby, as we soon learn in the film, was the favored sport of white South African’s during apartheid. To black South Africans it embodied everything that was wrong about the old regime.

Whether white or black, everyone agreed that the Springboks weren’t a great rugby team. They lost more matches than they won and had little to no chance in the upcoming Rugby World Cup. In fact, the only reason they were playing in it was that they had an automatic seat since South Africa was the host country. Mandela recognized that if he could help the Springboks to victory he could win favor with white South Africans and increased unity for the nation. And so that is what he set out to do. I commend the film for a feel good and yet meaningful movie night. For our purposes here, it is a clear example of someone working for their enemies’ happiness. While other leaders in Mandela’s circle wanted to destroy the Springboks as a symbol of the Apartheid regime, Mandela sought to give happiness to his enemies through helping the Springboks rise to victory.

Most of us won’t face a challenge of forgiveness and doing good for our enemies on the scale of Mandela. We weren’t imprisoned for 27 years for working to end our nation’s racist policies. But that doesn’t let us off the hook. Instead if someone who had so much justification for grievance chose to offer grace, we can certainly work to answer evil with good in our own small ways. Figuring out what this looks like is the task of discernment and discipleship. I can certainly think of a few situations in my own life where my fantasies of vengeance need to give way to generous grace. Whatever grace does come, I know it will not find its source in me. Instead it will come from the God on whom I wait, the Father in heaven who is “kind to the ungrateful and the wicked.”

I’ve been thinking about loving our enemies a lot lately, and what that actually looks like. I do believe that love and grace are the answer - when we realize that God offers every single person undeserved favor (grace) then we must also offer it ourselves. We can resist the opportunity to spread or encourage division and instead foster compassion and inclusion. It isn’t easy. And it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t stand up against injustice - it is HOW we protest that matters. Our behavior should manifest the fruits of the Spirit (patience included!) or we do not honor God.

Thank you for this, Ragan. I needed it today.