I have long been fascinated by the way the New Testament talks about the “Body of Christ” in three distinct ways—Incarnate, Eucharistic, and Ecclesial. There is the body of Christ in Jesus the Incarnate One, there is the body of Christ in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, and there is the Body of Christ as the Church. In the coming months I’ll be occasionally posting some reflections on these varied bodies. It will not be a systematic treatment, but I hope that in these explorations readers will find some help in experiencing the ways the infinite comes to dwell in the finite and particular. To get us started, here is a reflection on the journey of Evelyn Underhill into the institutional church.

In 1911, Evelyn Underhill published Mysticism, a monumental study of the human possibility of connection with the cosmic Oneness at the center of all things. Underhill, at the time, was involved in a growing spiritual awakening, a reaction against the disenchantment wrought by rapid industrialization and a materialistic scientific worldview. Hers was a time that saw a rise in new spiritualities, all promising connection with the Ultimate outside of “institutional religion.”

Underhill was a ready participant and promoter of such spiritual quests. She took part in occult groups and sought divine connections through a mysticism free from the tired trappings of institutional life. Eventually, however, the shine wore off, and Underhill went seeking a deeper source.

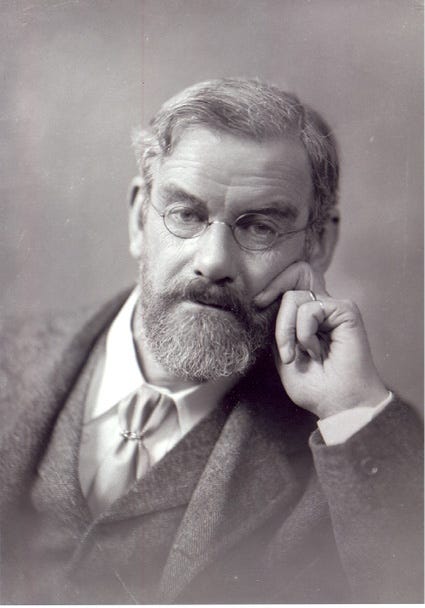

It was when she met the Baron Friedrich von Hügel that she found a guide to that deeper life. Baron von Hügel, a Roman Catholic scholar who had also written on mysticism (albeit of a sort rooted in institutional religion), became Underhill’s spiritual director. Among his key pieces of advice was that Evelyn become a member and participant in an institutional church.

The Baron, as he was known, did not have any rosy illusions about the difficulties of institutional religion. He went so far as describe church participation as a “hair shirt,” a kind of purposefully uncomfortable garment worn by monks seeking mortification of the flesh. Church could be a painful place, he told Underhill, and yet it was also a great teacher and source of real spiritual food that she could not do without.

As her biographer Robyn Wrigley-Carr puts it, as a result of von Hügel’s guidance, “Evelyn went from viewing the Church as being like a post office, with irritating, narrow-minded officials behind the counter, to ‘feel[ing] the regular, steady, docile practice of corporate worship’ as being the ‘utmost importance’ for ‘building up’ her spiritual life.” Underhill went on to argue that solitary prayer and personal spiritual devotions could not make up for the “humble immersion” in the “life and worship” of the Church.

Though the Baron was Roman Catholic, he encouraged Underhill in her journey into the Anglican Church. After her official entrance into institutional church life, Evelyn worshiped in a church twice a week for the rest of her life. As a result, the emphasis of her writings on spirituality changed significantly. While Underhill’s first major book was Mysticism in 1911, her magnum opus was Worship published in 1936. The two books represent her journey from a personal experience of Oneness to the corporate worship of God.

In his foreword to The Spiritual Formation of Evelyn Underhill, Eugene Peterson writes of Baron von Hügel’s metaphor for the spiritual like as a tree. The life of the tree, the source of its growth, happens both beneath the soil at the roots and beneath the bark through the cambium. The bark itself, what we see of a tree, is dead. But that dead bark is what protects the hidden life within and at the depths. So, said von Hügel, it is with the spiritual life. As Peterson summarizes it:

The Most intimate and intensely personal of all human activities is the life of the spirit - our worship, prayer and meditation, believing and obeying. But, without the protection of ritual, doctrine and authority, which it is easy (and common) to consider lifeless and dead, Christian spirituality is vulnerable to reduction and desecration.

In reading of Underhill’s journey, and the Baron’s wise counsel, I was reminded of our own time. Like England in the early 1900s, we live in an age of increased interest in spirituality. The cold rationalism of science has left us wanting and the empty satisfactions of material progress have not fulfilled our spiritual hungers. And yet, for many of us, the life of “organized religion” or the “institutional church” seem like more of an obstacle to fulfillment than the means to a spiritual feast. A hike in the woods or a Sunday morning relaxing at home may feel like more of what we need than going to the trouble of attending a worship service that leaves us feeling only mildly uplifted or even desperately dissatisfied.

And yet, beneath the bark—the gnarled, scarred, dead surface—the church continues to harbor life inside, life that can bubble up in surprising ways that sometimes don’t become apparent until you’ve spent a lifetime struggling inside the seemingly dry and dead confines of the surface.

For me, church is a chance to worship God with others in a way that goes beyond my preferences. I don’t get to pick the scriptures, I have little say over the liturgy or the music, and the building itself has its own opinions about what is possible. To be part of an institution is to be confined. But that, exactly, is the beauty of it. As Eugene Peterson writes, “A spirituality that has no institutional structure or support very soon becomes self-indulgent, subjective and one-generational.” This is a truth Evelyn Underhill recognized as she journeyed from disconnected mysticism into rooted worship.

As a finite, fleshly reality—the church is flawed and entangled with all the problems of incarnate life. Each Sunday morning, the church is full of broken people who do broken things, wounded people who wound. But by coming together with our wounded flesh, our fragile finitude to say our prayers, sing our hymns to God, eat together at the table of the Great Thanksgiving, we become participants in a source of life that moves mysteriously at the depths and surpasses all understanding.

It is a life that is subtle, slow, and quiet. Sometimes its movement is invisible, its work at a pace too slow to even see. That can be frustrating in a world of quick change, the rapid spew of screens and information. But like a tree, the life it brings to the surface, the hospitality it offers the world around it, the new air it produces from its patient work is unequaled by all the quick burning enterprises of our age.

It’s for that reason, early each Sunday, I get dressed, go to church, and join in another day of mundane worship. Some days I feel the life moving from the roots, some days I feel only the rough dead bark, either way I trust that this is the path toward growth, the continuation of Christ’s presence among us—His body incarnate in an institution as fragile, finite, and beautiful as flesh.

Thank you for giving us fresh eyes.

Ragan, this is superb! And I’d take things one step farther and say that the hairshirt metaphor applies not only to the church’s worship gatherings, but also to the church as community throughout the week, in all our efforts to embody Christ together… Thanks!!!